A clear focus

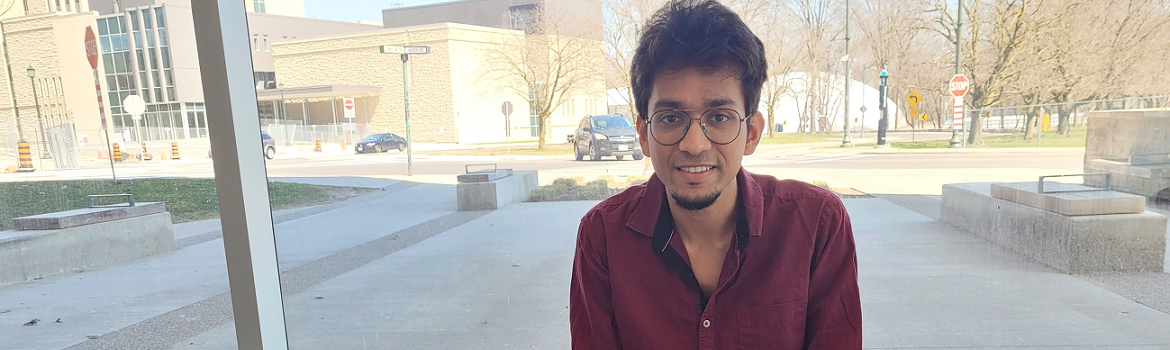

PhD student Santasil Mallik’s research will take a critical look at humanitarian crises beyond the camera lens.

By Cassie Dowse

When Santasil Mallik’s friend invited him to examine old photographs from her family’s shuttered photo studio, he didn’t imagine that evening would inspire a voyage across the globe, changing the course of his life forever.

At his friend’s home in Kolkata, India, Santasil dug through old photographs, cameras and tripods in hopes that something may prove useful in his work as a photographer. Though most he found were wedding photographs, there were many intriguing images taken during the independence movement from British colonial rule, a time when there were considerably less photographers in the country. Santasil was fascinated.

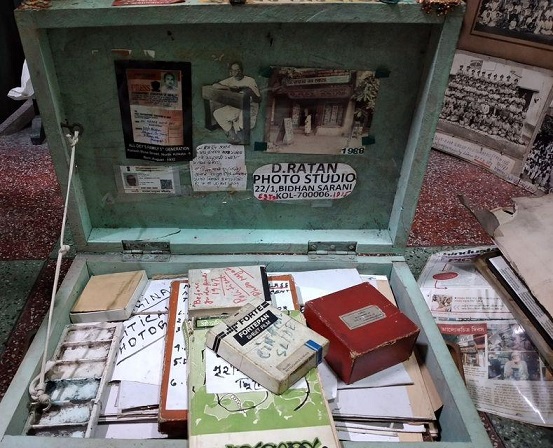

“There was a trunk covered in newspaper clippings. It had words written on the top that translated to, ‘In search for treasure,’” Santasil recalls. “My friend was always told not to touch it, so it remained closed for decades.”

As they opened the trunk, the two friends discovered a chilling trove of photographs of political protestors, killed during the independence movement. British state media refused to publish truths about the oppressive realities of life during that period. With colonial rule spanning from 1858 to 1947, many lives and stories became secrets, seemingly long forgotten. Santasil was captivated by the power dynamics behind those photographs.

“The photographs were poignant, but they revealed more than death,” he says. “I was struck by the politics of the images – who were being photographed and how were they framed, the scenarios behind the taking of the photographs, and the family’s decision to keep the trunk locked up for generations.”

Santasil started thinking about returning to school to study for a PhD and began searching for a university with aligned research interests. Having never left India before, he knew this would be a big change in his life, but he suddenly felt great pride and purpose – motivated by the complex legacy of photography in his country’s colonial past.

When he came across the work of Sharon Sliwinski, a Faculty of Information and Media Studies (FIMS) professor at Western, Santasil was intrigued by her human rights research and began the application process.

For Santasil, his time completing a master’s degree in English literature at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi was formative and advanced his penchant for helping others. The university has a reputation for a highly active political student culture – a generation of young people committed to not only bettering student life at the school, but debating important social issues that affect the country.

Always interested in visual arts, Santasil originally took up photography as a hobby and volunteered at events. As he began taking courses and attending documentary workshops in his spare time, the most intriguing questions he had were often centred on the medium itself, beyond the events through his lens.

“If we think about a video revealing human rights abuses, what we can’t see are the conditions that led to those events taking place,” he says. “I think about different possibilities behind those images – like politicians in a private room, signing a treaty that triggers a war.”

Santasil grew up in a family dedicated to helping marginalized people. For years, his father has worked at a hospital non-profit organization. Santasil became involved with the organization when India was disproportionately and tragically hit by COVID-19. To date, the World Health Organization estimates that over 530,000 people in the country have died during the pandemic.

“The health-care system in India crumbled during the pandemic, highlighting the tragic consequences of health inequity,” says Santasil. “As a volunteer photographer and videographer, it was my job to capture what was happening on the streets and in the slums where people continue to suffer to this day. I wanted to show these grim realities and hopefully raise money for the hospital that would translate to better patient care.”

Reconceptualizing the role of the camera in popular media

In 2020, Santasil wrote, produced and directed a documentary short, Farrago, that was featured at several international film festivals. The film reveals a disjointed, experimental format that begs for a more engaging critique of events by immersing the viewer in the narrative process.

“Typical documentary films are often formulaic, centred on the narrative of an individual or subject matter experts. The film’s producers and directors construct a digestible story arc for the viewer. Experimental filmmaking asks more of the viewer by presenting a collage of images and encouraging the audience to piece together what they can.”

The value of this, he says, is to force the viewer to look at violent imagery and social issues in a more humanitarian way. “With so much information at our fingertips, this is something that we, as audiences, are desensitized to. We need to reconceptualize the role of the camera in popular media and in conflict.”

The journey continues at Western

In addition to the opportunity to work with top-notch faculty, Santasil was drawn to Western for funding opportunities that were unmatched by other schools he applied to. Accepted in 2022, he was thrilled to study alongside some people whose research struck a chord, but moving across the world did pose challenges.

“As an international student, budgeting can be difficult,” he says. “I arrived in Canada to an empty boarding room, and I had to purchase everything I needed, including furniture.”

Santasil feels lucky to have been the recipient of the Catherine Sheldrick Ross Graduate Recruitment Scholarship, made possible by a legacy gift from the late FIMS dean. Gifts like Catherine’s, provided in a Will, play a key role in supporting Western by providing vital funding opportunities for students, faculty and researchers.

Santasil says the entrance bursary made him feel like someone had his back during an uncertain time away from friends and family. “A legacy gift means that someone’s positive influence extends well beyond their life, because they’re making a tangible difference for future students,” he says. “Catherine’s gift greatly eased the financial stress I felt when I arrived at Western.”

Though moving to London presented an entirely new environment for Santasil (with considerably colder winters), he soon felt at home with a warm, welcoming community of FIMS professors and students. The opportunity to work as a teaching assistant in a first-year undergraduate class has also been a meaningful experience. He hopes to one day be a professor or an educator at a non-profit organization, finding great value in working with youth.

“It is wonderful to speak with and guide students who are so engaged with course material,” he says. “They show up every week for insightful discussions and share how conversation topics resonate with their personal experiences.”

Santasil’s professor Sharon Sliwinski has allowed him the time and flexibility needed to define his research questions. “Professor Sliwinski has been an incredibly supportive supervisor,” he says. “People think of graduate school as such a scary, stressful thing, but I have found it to be a more fun and understanding environment than I could have imagined. I belong at Western.”

This story is featured in Western's 2023 Annual Impact publication.